When Quarkus meets Virtual Threads

Java 21 offers a new feature that will reshape the development of concurrent applications in Java. For over two years, the Quarkus team explored integrating this new feature to ease the development of distributed applications, including microservices and event-driven applications.

This blog post is the first part of a series of posts and videos demonstrating how to use virtual threads in Quarkus applications. The series covers REST, messaging, containers, native compilation, and our plans for the future. But first, let’s look at virtual threads, what they change, and what you should know about them.

The Java world before Java 21

At the beginning of the Java time, Java had green threads. Green threads were user-level threads scheduled by the Java virtual machine (JVM) instead of natively by the underlying operating system (OS). They emulated multithreaded environments without relying on native OS abilities. They were managed in user space instead of kernel space, enabling them to work in environments that do not have native thread support. Green threads were briefly available in Java between 1997 and 2000. I used green threads; they did not leave me with a fantastic memory.

In Java 1.3, released in 2000, Java made a big step forward and started integrating OS threads. So, the threads are managed by the operating system. It is still the model we are using today. Each time a Java application creates a thread, a platform thread is created, which wraps an OS thread. So, creating a platform thread creates an OS thread, and blocking a platform thread blocks an OS thread.

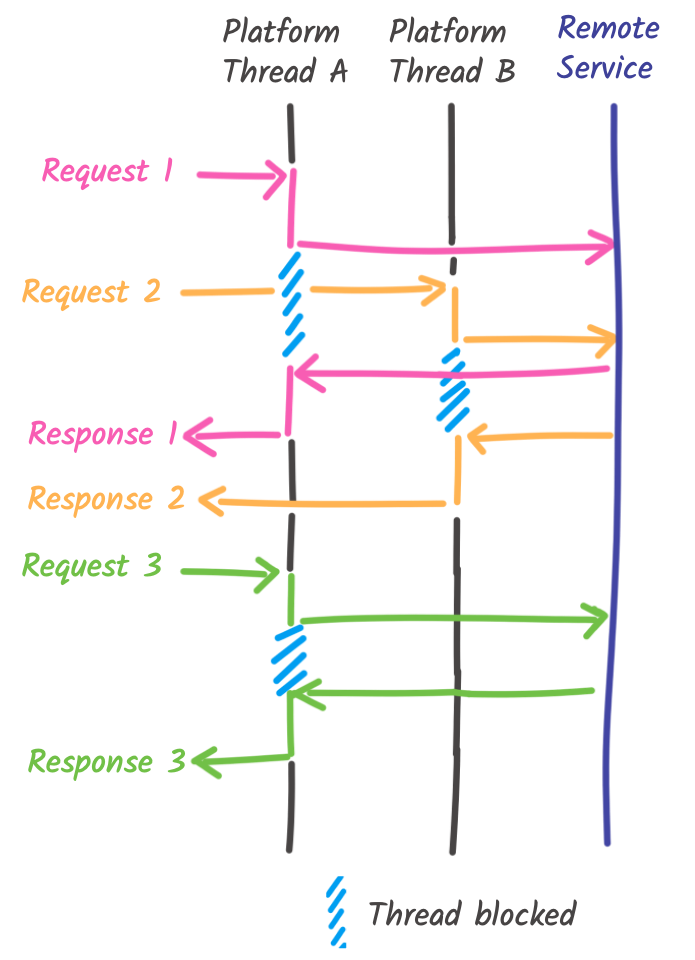

When you use a Java application framework, you rarely create threads yourself. It is done for you by the framework. For example, when your application receives an HTTP request, the framework creates or reuses a platform thread (and so an OS thread) and executes the processing on that thread. The whole processing runs on this thread, and the thread cannot be reused until the processing completes (so the response is sent back). When the processing executes a blocking I/O operation, like calling another service, writing to the file system, or interacting with a database, the thread is blocked, waiting for the response. As mentioned above, the OS thread is also blocked while waiting. When this response is received, the processing continues:

This model has the advantage of being simple to program with. The code follows an imperative model. The code is executed sequentially. It’s simple to write, simple to reason about. For example, the following snippet shows how you receive an HTTP request, call another HTTP service, and return a response with Quarkus. It follows the sequence diagram from above.

@Path("/greetings")

public class ImperativeApp {

@RestClient RemoteService service;

@GET

public String process() {

// Runs on a worker (platform) thread because the

// method uses a synchronous signature

// `service` is a rest client, it executes an I/O operation

// (send an HTTP request and waits for the response)

var response = service.greetings(); // Blocking, it waits for the response

// The OS thread is also blocked

return response.toUpperCase();

}

}But there is a limit to that imperative model. You can only handle n requests concurrently, with n the number of threads the framework can create. OS threads are expensive. They consume memory (around 1 Mb per thread), are expensive to create, use CPU to schedule them… Frameworks use thread pools to allow reusing idle threads, but when the concurrency level exceeds your number of threads, you start pilling up requests, increasing the response time, and, in the worst case, even rejecting requests. Increasing the thread pool size and, consequently, swelling the memory usage can blow up your Cloud bill and deployment density. Futhermore, adding more threads may not even improve the concurrency as explained by the Little Law.

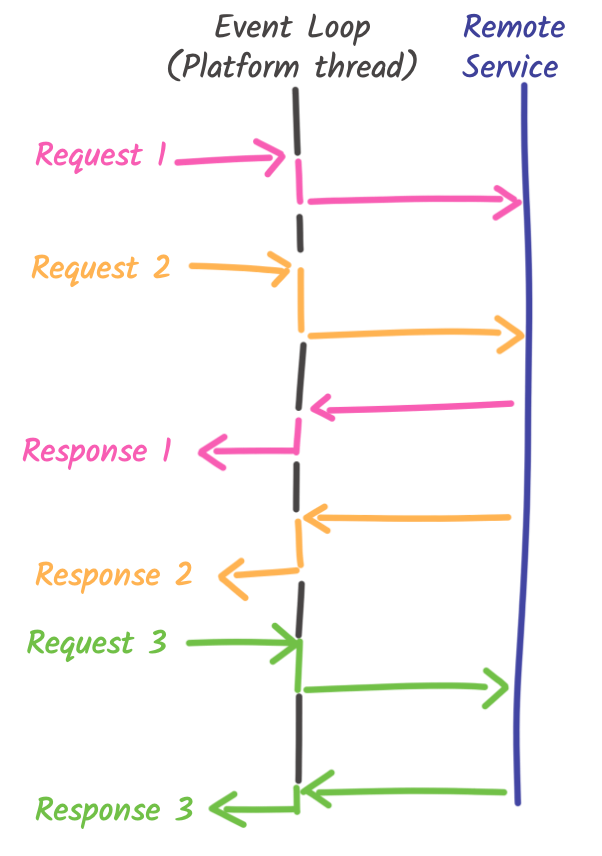

The reactive movement proposed an alternative model to work around that issue. It promotes the usage of non-blocking I/O and asynchronous development models to use resources (CPU and memory) more efficiently. With the reactive model, a single thread can handle multiple concurrent requests. So, instead of having a large pool of threads, you have a minimum number of threads (generally equal to the number of CPU cores). This small amount of threads, often named event loops, handles all your requests. When a request is received, it calls the processing code on one of these threads. When the processing needs to execute an I/O operation, instead of using blocking I/O, it schedules the operations and passes a continuation. This continuation is the code to be invoked when the I/O completes, so basically, the rest of the processing:

The reactive model is highly efficient, but there is a catch. As mentioned, you need to write your code as a chain of continuations. While there are multiple approaches, such as callbacks, futures, reactive programming, or co-routines, it makes the code harder to reason about. The code must be structured in a way that may not be natural for every developer. That limits the adoption of this solution. Also, the code can not only block during I/O operation; it must not execute lengthy processing (what we call monopolization). The model’s efficiency comes from the ability to process many requests concurrently. If the thread is used for a long time, it does not allow the other requests to be processed, and, as for the imperative model, you start piling up requests.

To illustrate the difference between the imperative and reactive model, the following snippet is equivalent to the previous one: it receives an HTTP request, calls another HTTP service, and returns a response. But this time, it uses the Quarkus reactive model.

@Path("/greetings")

public class ReactiveApp {

@RestClient RemoteService service;

@GET

public Uni<String> process() {

// Runs on an event loop (platform) thread because the

// method uses a asynchronous signature

// `service` is a rest client, it executes an I/O operation

// but this time it returns a Uni<String>, so it's not blocking

return service.asyncGreetings() // Non-blocking

.map(resp -> {

// This is the continuation, the code executed once the

// response is received

return resp.toUpperCase();

});

}

}An application with this code handles more concurrent requests and uses less memory than the imperative one, but, the development model is different.

Most of the time, the reactive and imperative models are opposed. This does not need to be the case. Quarkus uses a reactive core and lets you decide if you want to use the reactive or imperative model. Check the 'to block or not to block' article for more details about this ability.

What do virtual threads change?

Java 19 introduced a new type of thread: virtual threads. In Java 21, this API became generally available.

But what are these virtual threads? Virtual threads reuse the idea of the reactive paradigm but allow an imperative development model. You get the benefits from the reactive and imperative models without the drawbacks!

Like with green threads, virtual threads are managed by the JVM. Virtual threads occupy less space than platform threads in memory. Hence, using more virtual threads than platform threads simultaneously becomes possible without blowing up the memory. Virtual threads are supposed to be disposable entities that we create when we need them; pooling or reusing them for different tasks is discouraged.

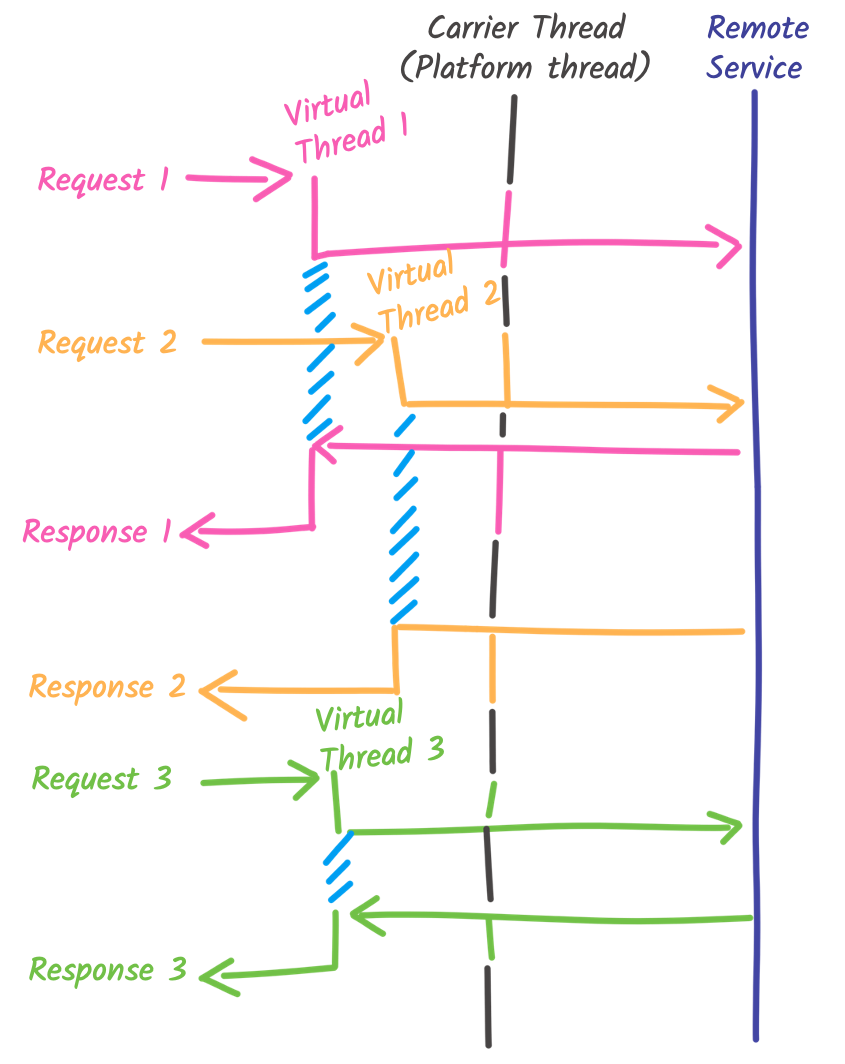

But what does it change? Blocking a virtual thread is, in general, very cheap! There is a pinch of magic that makes virtual thread very appealing. When your code running on a virtual thread needs to execute an I/O operation, it uses a blocking API. So, the code waits for the result, as with the imperative model. However, since the JVM manages virtual threads, no underlying OS thread is blocked when they perform this blocking operation. The state of the virtual thread is stored in the heap, and another virtual thread can be executed on the same Java platform (carrier) thread, exactly as in the reactive model. When the I/O operation completes, the virtual thread becomes executable again, and when a carrier thread is available, the state of the virtual thread is restored, and the execution continues. For the developer, this magic is invisible! You just write synchronous code, and it’s executed like proper reactive code without blocking the OS thread.

Your code runs on top of virtual threads, but under the hood, only a few carrier threads execute them.

To summarize, virtual threads are:

-

Lightweight - you can have a LOT of them

-

Cheap to create - no need to pool them anymore

-

Cheap to block when using blocking operations - blocking a virtual thread does not block the underlying OS thread when executing I/O operations

How can you use virtual threads in Quarkus?

Using virtual threads in Quarkus is straightforward.

You only need to use the @RunOnVirtualThread annotation.

It indicates to Quarkus to invoke the annotated method on a virtual thread instead of a regular platform thread.

This new strategy extends the smart dispatch explained in the 'to block or not to block' article. In addition to the signature, Quarkus now looks for this specific annotation. If your JVM does not provide virtual thread support, it does fall back to platform threads.

Let’s rewrite the same example using a virtual thread (the full code is available in this repository):

@Path("/greetings")

public class VirtualThreadApp {

@RestClient RemoteService service;

@GET

@RunOnVirtualThread

public String process() {

// Runs on a virtual thread because the

// method uses the @RunOnVirtualThread annotation.

// `service` is a rest client, it executes an I/O operation

var response = service.greetings(); // Blocking, but this time, it

// does neither block the carrier thread

// nor the OS thread.

// Only the virtual thread is blocked.

return response.toUpperCase();

}

}It’s the code from the first snippet (the imperative one), but its execution model is closer to the reactive one:

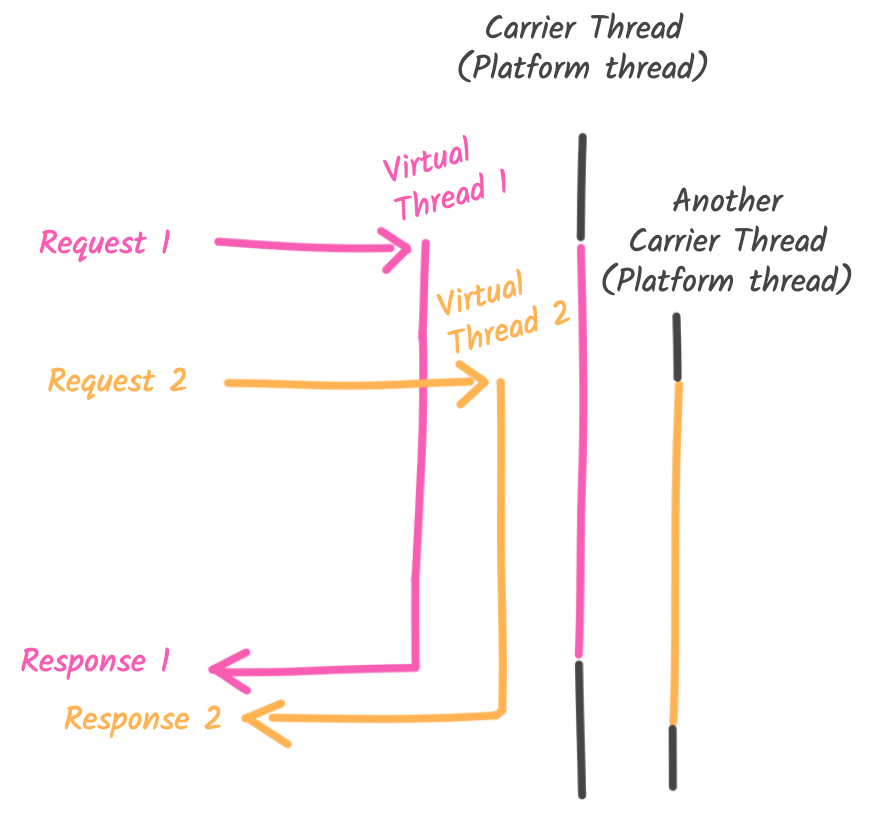

For every request, a virtual thread is created. When a carrier thread is idle, the virtual thread is mounted on that carrier thread and executed. When the virtual thread needs to execute the I/O (the call to the remote service), it only blocks the virtual thread. The carrier thread is released, and can mount another virtual thread (like the one handling the second request while the I/O from the first one is pending). When the I/O completes, a carrier thread (not necessarily the same one) restores the blocked virtual thread and continues its execution until the response is ready to be sent back to the client. The code snippet works as described because the Quarkus REST client is virtual-thread-friendly; we will see exceptions in the next section.

Virtual threads in Quarkus are not limited to HTTP endpoints. The following snippet shows how you can process Kafka/Pulsar/AMQP messages on virtual threads:

@Incoming("events")

@Transactional

@RunOnVirtualThread

public void persistEventInDatabase(Event event) {

event.persist(); // Use Hibernate ORM with Panache

}Attentive readers may have seen that the virtual thread integration relies on reactive extensions.

These extensions provide more flexibility (such as the control on which thread the processing is executed) to integrate virtual threads properly and efficiently.

It’s important to understand that for the developer, it’s invisible (except the @RunOnVirtualThread annotation).

Five things you need to know before using virtual threads for everything

Well, you probably see this coming. There is no free lunch. You need to know a few things before utilizing virtual threads for everything. These are the reasons why, currently, there is no global switch to run exclusively on virtual threads in Quarkus.

1. Pinning

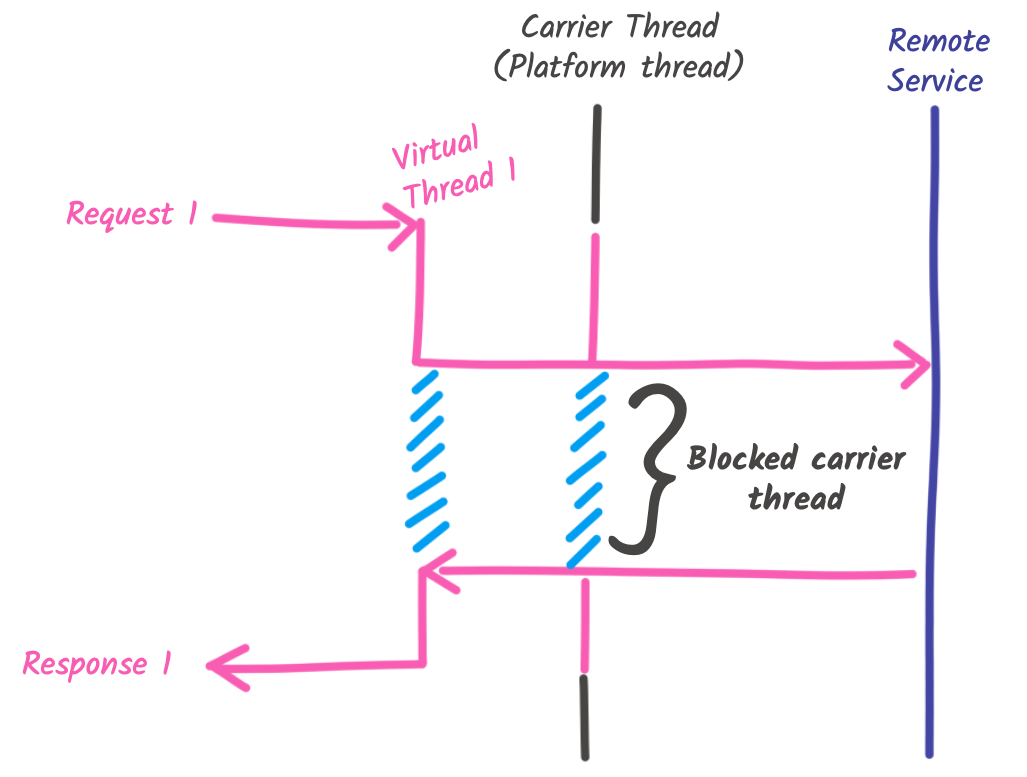

As described above, when a virtual thread executes a blocking operation, it gets unmounted from the carrier thread, preventing the carrier thread from being blocked. However, sometimes, the virtual thread cannot be unmounted because its state cannot be stored in the heap. It happens when the thread holds a monitor lock or has a native call in the stack:

Object monitor = new Object();

//...

public void aMethodThatPinTheCarrierThread() throws Exception {

synchronized(monitor) {

Thread.sleep(1000); // The virtual thread cannot be unmounted because it holds a lock,

// so the carrier thread is blocked.

}

}In this case, the carrier thread is blocked, so the OS thread is blocked:

Unfortunately, as of today, lots of Java libraries are pinning the carrier thread. The Quarkus team and Red Hat, in general, have patched many libraries (such as Narayana (the transaction manager of Quarkus) or Hibernate ORM) to avoid pinning. However, when you use a library, be careful. It will take time until all the code gets reworked in a more virtual-thread-friendly way.

2. Monopolization

As for the reactive model, if the virtual thread executes intensive and long computation, it monopolizes that carrier. The virtual thread scheduler is not preemptive. So it cannot interrupt a running thread. It needs to wait for an I/O or the completion of the computation. Until then, this carrier thread cannot execute other virtual threads:

Using a dedicated platform thread pool might be wiser when executing long computations.

3. Carrier thread pool elasticity

When there is pinning or monopolization, the JVM may create new carrier threads (as illustrated on the previous picture) to avoid having too many unscheduled virtual threads.

These creations are creating platform/OS threads. So, it’s expensive and uses memory. You especially need to pay attention to the second point. You may hit the memory limit if you run on low resources and your code is not very virtual-thread-friendly, meaning that you should always check for pinning, monopolization, and memory usage. If you don’t, in a container with memory constraints, the application can be killed.

4. Object pooling

For years, threads were scarce resources. It was recommended to pool them and reuse them. This good practice has encouraged the use of thread locals as an object-pooling mechanism. Like Jackson or Netty, many libraries store expensive objects in thread locals. These objects can only be accessed by the code running on the thread in which the objects are stored. Because the number of threads was limited, it capped the number of creation. Also, because threads were reused, the objects were cached and reused. Unfortunately, these two assumptions are not valid with virtual threads: You can have a lot of them, they are not reused. It’s even discouraged to pool them. Thus, libraries utilizing these pooling patterns may underperform when using virtual threads. You will see many allocations of large objects, as every virtual thread will get its own instance of the object.

Replacing this pattern is not an easy task. As an example, this PR from Mario Fusco proposes an SPI for Jackson. Quarkus will implement the SPI to provide a virtual-thread-friendly pool mechanism.

5. Stressing thread safety

Virtual threads provide a new way to build concurrent applications in Java. You are not limited by the number of threads in the pool. You do not have to use asynchronous development models.

But, before rewriting your application to leverage this new mechanism, ensure the code is thread-safe. Many libraries and frameworks do not allow concurrent access to some objects. For example, database connections should not be accessed concurrently. You must be cautious when you have many virtual threads, especially when using the structured concurrency API (still in preview in Java 21).

When using structured concurrency, it becomes easy to run tasks in parallel. However, you must be absolutely sure that these tasks to not access a shared state which do not support concurrent access:

@GET

@RunOnVirtualThread

public String structuredConcurrencyExample() throws InterruptedException, ExecutionException {

var someState = ... // Must be thread-safe, as multiple virtual thread will access

// it concurrently

try (var scope = new StructuredTaskScope.ShutdownOnFailure()) {

var task1 = scope.fork(() -> {

// Run in another virtual thread

return someState.touch();

});

var task2 = scope.fork(() -> {

// Run in another virtual thread

return someState.touch();

});

scope.join().throwIfFailed();

return task1.get() + "/" + task2.get();

}

}Summary and what’s next

This post described the new kind of thread available in Java 21 and how to use them in Quarkus. Virtual threads are not a silver bullet, and while they can improve the concurrency, there are a few limitations you need to be aware of:

-

Many libraries are pinning the carrier thread; it will take time until the Java world becomes virtual-thread-friendly.

-

Lengthy computations must be analyzed cautiously to avoid monopolization issues.

-

The carrier thread pool elasticity may result in high memory usage.

-

The thread-local object polling pattern can have terrible consequences on the allocations and memory usage.

-

Virtual threads do not prevent thread safety issues.

It is the first part (and the most boring, hopefully) post of a multiple-post series. Next, we will cover:

-

What are we exploring to improve the virtual thread support in Quarkus (to be published)

To know more about the virtual thread support in Quarkus, check the Virtual thread reference guide.