How Quarkus has been used to deploy applications on OpenShift

This post gives some feedback on a particular challenge I have been facing in a professional context with respect to deploying applications on Kubernetes, and how we were able to provide a solution that met our goals using Quarkus.

The challenge

For a few years now I have been involved in a Kubernetes project, aiming at:

-

Onboarding more easily and more quickly new technologies (either applicative frameworks, or middleware products).

-

Lowering the administrative burden of deploying distributed inter-related services by creating a logical deployment abstraction on top of these services; something like the umbrella chart pattern.

-

Limiting the work needed by an application team to deploy a component, and hyper-standardize Kubernetes deployment objects.

-

Transitioning to an hybrid cloud deployment model.

In addition to those goals, there was a constraint related to the fact that applications may be deployed by tenant (i.e. they are not multi-tenant, for different reasons, some being regulatory related). Depending on the application, there may be a few dozens tenants, which would translate into deploying the application once per tenant (so if we had 10 tenants for an application, there would be 10 processes running in production). However, if processes needed to be physically separated, often some portions of configuration could be shared between some tenants, and/or IT environments, and/or geographical zones according to different business rules. Highly simplified and factorized bits of configuration would be a true source of simplicity for the development team, and a true source of complexity for the deployment process.

Some projections indicated that at project end, the different clusters in production would contain 10'000 pods.

First attempts

Given that complexity we created our own tool for configuration and deployment. The initial version was based on Ansible and ran into Tower workflows. For different reasons we decided to rewrite it in Java a year ago, mainly to:

-

Get better performances.

-

Use a high level language that could cope with algorithm complexity.

-

Get better support for unit and integration testing.

-

Improve productivity with quality development tools (e.g. IDE).

One thing we were concerned about though, was memory consumption, CPU usage and startup times since for a given application, each tenant is deployed in isolation in its own deployment process. For that reason we decided to not depend on any application framework when we started the Java rewrite, because if they do offer productivity and standardization, the abstraction they provide comes with a resource cost. So the program was written in plain Java, and it was small enough in size and use cases that we were able get away with it, provided we relied on a few patterns (e.g. constructor based injection by hand) for clean code. This program is called ocpdeploy.

As we were moving away from Tower, we decided to leverage our Kubernetes infrastructure by running ocpdeploy as tasks in Tekton pipelines. This gave us repeatability, a way to deploy different applications, or even different tenants for the same application with different ocpdeploy versions. The use of java (any other high level language would have been a good fit) provided us with a high level of productivity, and maintainable code, while being able to implement complex algorithms for configuration processing, and raised the level of quality of ocpdeploy releases thanks to our extensive regression testing suite.

All was well… until we started deploying multiple tenants at the same time, and/or different applications. We had sized the ocpdeploy container to 200 millicores and 280 Mb of RAM. For some applications there were around 30 tenants, that would be all deployed in parallel. This meant 30 pods, which accounted for 6 cores and 8 Gb of RAM. This seems livable, but deployments tend to be done after business hours, between 7 and 8pm for many. And we started being afraid of the impact ocpdeploy itself would have if we were running multiple deployments in parallel, on top of our SpringBoot or WildFly applications, which take their toll on the cluster at startup.

Enter the Quarkus Universe

So less than a year ago we decided to launch a Quarkus POC on ocpdeploy, the goal being to deploy it as a GraalVM executable. The main challenges we ran into were related to the lack of support for GraalVM in some of the libraries we were using: FreeMarker, SMBJ (a java client library that implements the Server Message Block SMB2 and SMB3 protocols), the Fabric8 OpenShift client (when instantiating OpenShift specific CRDs), and a home made java agent that ships logs to a proprietary centralized logging system.

Fortunately, other bits were already there in Quarkus, such as support for command mode applications, a rest client, the Vault extension, and support for the Fabric8 Kubernetes Client, which provided a nice base for a new OpenShift Client extension that was added to the core. The Kubernetes Client extension alone was a huge push for the project because when we started we did not have Argo available, so we had to implement apply and prune ourselves.

For FreeMarker we pushed a new extension to the Quarkiverse, with code largely inspired from work by ppalaga and carlosthe19916.

For SMBJ we created an extension in our internal Quarkiverse. And for our logging client, I was able to draw some inspiration from the quarkus-logging-gelf extension, and created an additional internal extension.

Getting a library to run in native was facilitated by the very good documentation that comes from the Quarkus project and support in the framework (e.g. processors and recorders): Supporting native in a Quarkus extension.

When things got a little hairy (SMBJ was trickier than we thought), we got some help from the GraalVM tracing agent.

Here is the list of extensions that we happened to use: cdi, config-yaml, freemarker, hibernate-validator, kubernetes-client, openshift-client, rest-client, restclient-jackson, vault (plus internal extensions for SMBJ and our internal centralized logging system).

Eventually we got all the required libraries to work in native mode, and we could switch efforts toward migrating the application to look like a real Quarkus application:

-

Using injection, with qualifiers and producers when necessary.

-

Rewriting tests to use the different mocking approaches, including the new (at the time) QuarkusTest profiles.

This allowed us to provide extensive testing through Kubernetes yaml generation, snapshotting and replay in a variety of situations transforming all the configuration to be MP config compliant.

Benchmarks

Then, we ran some benchmarks to assess resource consumption compared to the old version. We were not really worried about startup time. We knew it would be very good. And as long as it stayed in the few seconds window (which we were experiencing on the plain Java version), we were OK. But memory and CPU consumption was another story. The whole exercise was motivated by hopes for some real gains.

With the plain Java version we were able to squeeze the container down to 180 Mb (below that it would either go OOM, or the GC would kill the performances). And for the native version, we were able to go as low as 50 Mb.

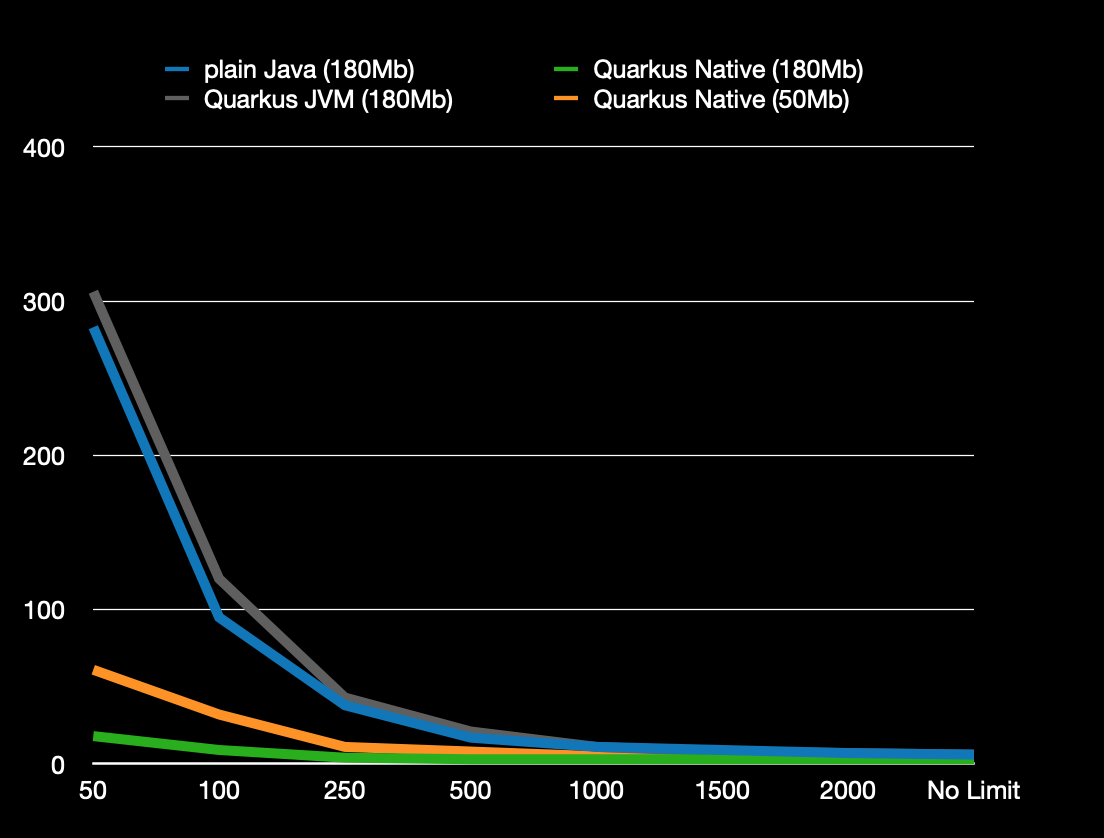

Then we executed several runs with different configurations (plain Java 180 Mb, Quarkus native 180 Mb, Quarkus jvm 180 Mb, Quarkus native 50 Mb , starting from 50 millicores request=limit, moving up to 100, 150, …

At 50 millicores, Quarkus native 180 Mb would run in 20 seconds, Quarkus native 50 Mb in 60 seconds, and the others 2 in 300 seconds. This meant that if we allowed 180 Mb to ocpdeploy, we could go from 300 to 20 seconds. A x15 times improvement.

At 250 millicores we had Quarkus native 180 Mb under 5 seconds, Quarkus native 50 Mb at 10 seconds, and the 2 others around 40 seconds.

We searched also how much CPU was needed to get a deployment under 60 seconds.

For Quarkus native 50 Mb it was 50 millicores, for plain Java 180 Mb and Quarkus jvm 180 Mb it was 240 millicores (Quarkus native 180 Mb was out of scope since its "worst" result was 20 seconds as discussed in the first test). This meant that if time was our constraint, we could go from 240 millicores to 50 millicores, while going from 180 Mb to 50 Mb by moving to Quarkus native.

The comparison between Quarkus native 180 Mb and 50 Mb was interesting as well, because it showed that by pushing up and down the memory and CPU knobs we could work on the use case execution duration. It was then up to us to decide where was the sweet spot between execution time and resource consumption.

The last interesting observation we made was that the results for plain Java 180 Mb were nearly identical to Quarkus jvm 180 Mb. This meant that the cost of the applicative framework, which provides maintainability and productivity, was 0 in our case. It’s like having your cake and eating it as well. In our case we did not mind slow executions, as long as we could save a lot on memory and CPU, which we were able to achieve.

Program execution in seconds for different limits (in millicores)

| plain Java (180Mb) | Quarkus Native (180Mb) | Quarkus JVM (180Mb) | Quarkus Native (50Mb) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

50m |

283 |

18 |

306 |

61 |

100m |

95 |

9 |

120 |

32 |

250m |

38 |

4 |

43 |

11 |

500m |

17 |

3 |

21 |

8 |

1000m |

11 |

3 |

11 |

5 |

1500m |

9 |

3 |

8 |

5 |

2000m |

7 |

3 |

7 |

5 |

No Limit |

8 |

3 |

6 |

5 |

A few issues

Beside the challenges of running ad hoc libraries in GraalVM, there were a few unexpected behaviors or minor pain points we ran into, such as:

-

Missing warning on unknown application configuration property #14889

-

Default on config pojo should behave the same if set in

src/main/resources/application.yaml#13423 -

Warn or fail if an application.yaml is provided without the

quarkus-config-yamldependency #13227 -

Upgrade to MP Rest Client 2.0 #10520, which we have been waiting for, to get "follow redirects"

-

I wished there was a way to define mock alternatives per test through annotation, but this was answered in this thread

-

Inability to provide certificates at run time instead of build time (GraalVM limitation) #3091

-

Visibility of

src/main/resources/application.propertiesin test as discussed in this thread; A lot of work has been done since then such as "Use AbstractLocationConfigSourceLoader to load application.properties and application.yaml" #15282, so I need to recheck -

Optional config property overriden with empty value as discussed in this thread

-

Quarkus YAML configuration keys are implicitly escaped #11744

-

Warn or fail if an application.yaml is provided without the

quarkus-config-yamldependency #13227

This seems quite a bit, but actually none of those bullet points were major issues, or something we could not work around. Several issues were related to configuration, in part because the program was run as a Tekton task, and there is limited flexibility on how you define optional parameters in Tekton. I have listed only those points that we had to work around. Many issues or questions were actually resolved as we were making progress through answers in the google group, or actual fixes.

CI for native builds

Another challenge was related to native build time, memory and CPU usage during those builds. The approach we took was to only generate a native executable on master, and run tests in jvm mode on the feature branches. We would still have an option to test against native in a particular feature branch if we needed to. But unless we were integrating a new library, getting the jvm tests to pass gave us sufficient confidence that we would have an identical behavior in native.

The other trick we applied was to cancel the current build on master if a new one got triggered; that way we would not have multiple native builds running at the same time. In theory it could be frustrating to get a build killed because another commit was done. In practice this was not an issue because the rate of PRs getting merged on master stayed low.

But there are definitely some questions around sizing a build infrastructure if we had wanted to increase the number of Quarkus applications developed internally.

The only drawback compared to the original solution was that our regression test suite was slower to run, essentially because our tests generated resources in the context of a specific configuration. And since we were using MP config, we needed to boot a new Quarkus context every time we wanted to test a different configuration. Fortunately booting a new context is extremely fast in Quarkus, but still a lot slower than with our original plain Java solution.

It is all about the community

Beside work on the Vault, FreeMarker and OpenShift Client extensions, we started contributing a few PRs in and outside Quarkus, hoping to speed up the process of getting improvements, such as:

-

Add

appendResourceVersionInObjectfor CRD objects #2365 (merged) -

Add cert-manager extension support #2930 (merged)

-

Build distroless image using cekit in ci #118 (merged)

-

Allow root certificates to be configured at run time of native image #3091 (teshull assigned by Christian Wimmer at Oracle to work on this for the GraalVM 21.3 release)

It is worth noting that the Quarkus community has been a huge factor for success, by:

-

Answering questions on the google group, zulip or other means such as stackoverflow.

-

Investigating issues in a timely fashion, and depending on the situation either providing fixes, guidance on applying the right approach, or workarounds.

-

Being open to improvements (e.g. on configuration).

-

Reviewing PRs quickly, and facilitating contributions.

-

Releasing with high frequency.

Takeovers

It took us only a few months to do the migration, and we started deploying our first OpenShift application with our Quarkus powered ocpdeploy end of last year. Since then, it was used to run hundreds of deployments. We were able to follow the pace of new releases with limited effort. We incurred very few bugs, usually fixed in time for the next release. The applicative framework provided by Quarkus allowed us to better structure our code, making it more maintainable, and easy to tests with mock features and test profiles. It is interesting to note as well that ocpdeploy development was done by team members that were not Quarkus developers, or even strong Java specialists. This is a sign that the framework is light enough that once the overall structure (e.g. components, tests, configuration, ci) is in place, we can forget about it.

Our program was not business critical in the sense that if it did not work, business would not stop. But it is the only mean to deploy all of our OpenShift microservices. And given the pace of internal developments, it is considered a critical piece in the value chain. ocpdeploy is not evidently ultra sophisticated, and we only scratched the surface of what could be done with Quarkus, but yet it worked for us, showing that it can tackle many different use cases.

In conclusion, I think the strong selling points for Quarkus are:

-

A vivid community, which listens actively for feedback, and welcome contributions

-

A project developed with high velocity

-

The right positioning (cloud native, developer joy, …) with versatility

-

Willingness to pragmatically bend, a little, specifications when they would work against the Quarkus values

-

An architecture with a compact core and extensions, allowing for rapid expansion, which will nurture innovation

-

Support for native by default, but also some improvements in jvm mode also

-

Fast growing eco-system through the core extensions, the universe extensions (e.g. camel) and the Quarkiverse

-

Dev mode (local and remote)

-

A framework for developing extensions that facilitate implementing patterns such as the build time initialization

The main challenge I see going forward, similarly to app stores 10 or 15 years ago, is to make sure that the extension eco-system grows in quantity without sacrifice for quality. Or at least provide a way to rate extensions, so that people building business critical applications get assurances that their investment in the technology is sound. In other words going deep in addition to going wide. The other challenge I see is progressively filling the gaps of enterprise readiness; for instance finishing up solutions sometimes partially developed today, and making sure there is a clear and mature solution for the most common use cases.

That is how Quarkus will win over enterprises. And I can see this being in motion.

I am very hopeful for the project. Can’t wait to expand the use cases.